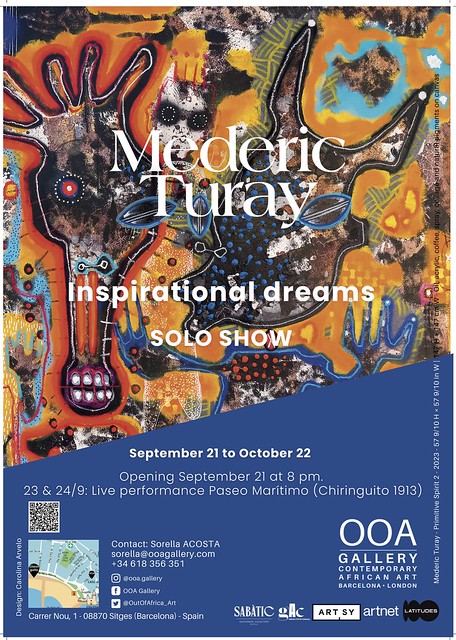

The new exhibition at the Out of Africa Gallery hosts Mederic Turay’s Solo Show, “Inspirational Dreams,” from September 23rd to October 22nd, 2022.

The opening will take place on September 21st at 8:00 pm.

Presentation / Talk at the Hotel Sabàtic on Friday, September 22nd at 6:00 p.m.

On September 23rd and 24th, live performance on the Paseo Marítimo (Chiringuito 1913), from 11 a.m. to 6 p.m

Mederic Turay

Born in 1979, in Abidjan, Ivory Coast. Lives and works in Marrakech, Morocco.

Mederic Turay’s artistic journey is marked by a fusion of influences from hi childhood, upbringing in Norht American urban culture and the roots of his African heritage. His passion for art began at an early age, and he has evolved into a multifaceted artist whose work spans paintings and sculptures.

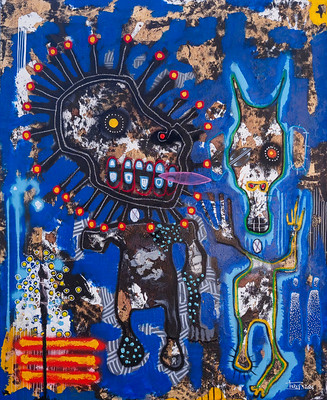

His art showcases vibrant colors and intricate designs that draw viewers in. Mederic employs varios techniques, including collage and distortion of form, to create a bridge between realism and abstraction. He incorporates elements from African primal arts, such as masks and totemic figures, to convey the spiritual and supernatural dimensions of his art. His pieces serve as explorations of life, death, and consciousness, evoking a poetic and philosophical perspective on existence.

Through his creative process, Mederic Turay aims to capture the essence of life’s complexity, intertwining personal narratives and universal themes. His art invites viewers to explore the interplay between the visible and invisible worlds. His works pay homage to his African heritage while engaging with contemporary artistic trends.

Mederic Turay: A Dream That Never Ends

By Marga Perera

With over 40,000 followers on Instagram, only 75 posts, and some of them with 5,000 likes; he also has a YouTube channel where you can watch videos of his exhibitions, painting graffiti, promoting a beer ad while wearing one of his self-designed blazers adorned with his personal iconography – some of which are already in the possession of his privileged collectors – or even dancing with spectacular grace and rhythm. It’s clear that he is one of the young artists of the moment. He is Mederic Turay (Ivory Coast, 1979), who was chosen as the Best Young Artist of West Africa in 1999. His passion for art began as a child; at the age of 4, he was already drawing, imitating characters from cartoons and works by Picasso, Dalí, and Basquiat. He grew up immersed in North American urban culture because his father, a military man by profession, accepted a mission in Washington in 1984. So, Mederic experienced the golden era of hip-hop (the so-called “Hip Hop Golden Era”) in America, where he embraced dance as a form of bodily expression, rapping, and graffiti art. This cultural explosion clearly influenced the natural evolution of his work. In 1995, his family returned to Ivory Coast, and Mederic began his studies in Fine Arts, where he discovered the roots of his culture, which have been manifested through his art. These two worlds, which are part of his life experience, coexist harmoniously in his work. He is convinced that life transformed him into an artist because he believes that art remains the ultimate expression of life. One of his mottos is: “Inspire yourself to pursue your dreams; then nothing can stop you.” He is represented in prestigious collections such as Charles Saatchi’s, the King of Morocco, Mohamed VI’s, and the Niarchos Collection in Switzerland.

With over 40,000 followers on Instagram, only 75 posts, and some of them with 5,000 likes; he also has a YouTube channel where you can watch videos of his exhibitions, painting graffiti, promoting a beer ad while wearing one of his self-designed blazers adorned with his personal iconography – some of which are already in the possession of his privileged collectors – or even dancing with spectacular grace and rhythm. It’s clear that he is one of the young artists of the moment. He is Mederic Turay (Ivory Coast, 1979), who was chosen as the Best Young Artist of West Africa in 1999. His passion for art began as a child; at the age of 4, he was already drawing, imitating characters from cartoons and works by Picasso, Dalí, and Basquiat. He grew up immersed in North American urban culture because his father, a military man by profession, accepted a mission in Washington in 1984. So, Mederic experienced the golden era of hip-hop (the so-called “Hip Hop Golden Era”) in America, where he embraced dance as a form of bodily expression, rapping, and graffiti art. This cultural explosion clearly influenced the natural evolution of his work. In 1995, his family returned to Ivory Coast, and Mederic began his studies in Fine Arts, where he discovered the roots of his culture, which have been manifested through his art. These two worlds, which are part of his life experience, coexist harmoniously in his work. He is convinced that life transformed him into an artist because he believes that art remains the ultimate expression of life. One of his mottos is: “Inspire yourself to pursue your dreams; then nothing can stop you.” He is represented in prestigious collections such as Charles Saatchi’s, the King of Morocco, Mohamed VI’s, and the Niarchos Collection in Switzerland.

At first glance, his paintings are attractive due to their lush colors that captivate the viewer’s gaze. The eye cannot help but be drawn in, not just by the colors, but by a labyrinthine “horror vacui” that compels one to explore the entire canvas. This can be seen as a metaphor for a quantum universe in which everything is interconnected, representing a metaphor for reality itself – a reality that we don’t always see. His paintings are like treasure maps where there is much to discover. He says he paints the noise that surrounds him and creates his own inner landscape because when he paints, he feels compelled to cover every inch of the canvas without pause. I believe this “feeling guided” corresponds to inner strength, the creative impulse Carl Gustav Jung spoke of when he discovered the “autonomous complex,” which he defined as a split-off portion of the psyche that leads its own life outside the hierarchy of consciousness. Therefore, the creative process has a conscious aspect – intention – and an unconscious aspect. With this compulsion to paint without pause, Mederic creates a territory that connects his multiple experiences, both personal and collective, encompassing diverse cultures, urban art, and primitive art, as well as his own influences as an artist, past and present, life and death, showcasing opposites as inseparable parts of unity, mirroring the reality of the Universe.

Mederic plays with the distortion of form, the relationship between figure and background, the gradient of size to suggest depth without relying on perspective, the impact of color, and collage, which introduces the stability of the concrete into an abstract setting. All his characters appear crowned. For Mederic, who confesses to a strong belief in the presence of crowns around a living being, whether human or animal, this is interpreted as a manifestation of what we radiate to others and the world – something he would describe as an aura, thereby delving into the realm of the spiritual. Collages of sculptures from African primal arts coexist with his abstract representations of humans and animals; they are smaller in size, as if they are further away in space and time. In reality, they represent the past in the present because time and its evolution are not linear. Formally, these collages for Mederic are a way to play with fullness and emptiness, realism and abstraction. Conceptually, it’s a way to create a connection between spirits and humans, bridging the invisible and the visible. His desire to ascend to the world of the invisible explains the significant presence of masks in his paintings, as in African religious rituals, masks represent the supernatural.

Mederic plays with the distortion of form, the relationship between figure and background, the gradient of size to suggest depth without relying on perspective, the impact of color, and collage, which introduces the stability of the concrete into an abstract setting. All his characters appear crowned. For Mederic, who confesses to a strong belief in the presence of crowns around a living being, whether human or animal, this is interpreted as a manifestation of what we radiate to others and the world – something he would describe as an aura, thereby delving into the realm of the spiritual. Collages of sculptures from African primal arts coexist with his abstract representations of humans and animals; they are smaller in size, as if they are further away in space and time. In reality, they represent the past in the present because time and its evolution are not linear. Formally, these collages for Mederic are a way to play with fullness and emptiness, realism and abstraction. Conceptually, it’s a way to create a connection between spirits and humans, bridging the invisible and the visible. His desire to ascend to the world of the invisible explains the significant presence of masks in his paintings, as in African religious rituals, masks represent the supernatural.

The characters that inhabit his canvases, radiating with their auras and vibrations, have various and powerful gazes, serving as examples of non-verbal language. These are eyes with X-shaped crosses, dots, iridescent circles, coffee grains, swirling lights, conveying different messages while looking at the viewer and in all directions. Through his characters, Mederic aims to evoke both life and death simultaneously. He believes that it’s the intensity of self-awareness, the definitive nature of self-discovery, that prepares and enables the “timelessness” of death. He has a poetic vision of life and death: “Small deaths fragment throughout our lives. The same abyss widens, the same vertigo recoils at the evocation of one and the other. The self and death are twin mirrors. With the veil removed, they meet in a kind of incestuous embrace. The resulting destruction is not necessarily just physical death; it’s also mental death, hallucination, and madness – an image of spiritual death.” It’s like contemplating death on this earth as a transition to another plane, with an awakening of consciousness. Therefore, through his art, Mederic draws an arc that could range from the solar disks in African rock paintings to more metaphysical, philosophical, and spiritual questions.

His art is infused with an intriguing conceptual and philosophical perspective on the invisible world – a world that, despite its presence, is not easily perceptible. Thus, he turns to primitive art as the first representation of humans and animals in all their authenticity, harkening back to the era of cave paintings. These totemic presences – applied through collage – act as a revisiting of traditional African religions with their totems, which are such magical and powerful entities that they can create connections between animals or plants and groups or individuals within a clan. Mederic constantly sees the two sides of the same reality, and these totemic presences in his paintings serve as witnesses of time, narrating the story alongside him. They represent the primitive spirit, a reminder of his ancestors and traditions. His works are inspired by African fables or poetry, infusing the sacred into his contemporary creations.

His work is rich in meaning because it attempts to explore the complexity of humanity through our evolutionary and cultural history. Therefore, his paintings are populated with numerous human references, with characters who carry their personal stories within them, such as joy, sadness, or love – common emotions and feelings experienced in different ways in a world that we still struggle to fully comprehend.

His work is rich in meaning because it attempts to explore the complexity of humanity through our evolutionary and cultural history. Therefore, his paintings are populated with numerous human references, with characters who carry their personal stories within them, such as joy, sadness, or love – common emotions and feelings experienced in different ways in a world that we still struggle to fully comprehend.

In addition to the contemporary spirit of his art, Mederic is deeply connected to “Alkebulan,” as his ancestors called Africa, which means “Garden of Eden” or “Mother of Humanity.” He acknowledges that Alkebulan, as the search for the origin of humanity, is an eternal source of inspiration for him as an artist. Years ago, I studied the astonishing rock paintings of Tassili in the Sahara Desert. It’s still a mystery which civilization could have created them around 10,000 years ago – some sources even suggest 12,000 years. These enigmatic depictions include human figures, boats, hippos, rhinoceroses – animals that require a lot of water to survive. The realism is so convincing that it’s believed they could only have painted them that way if they could actually see these creatures there. Africa was a lush paradise back then, with abundant rivers and lakes, comparable to our idea of the Garden of Eden. I asked Mederic if he was familiar with Tassili; he hasn’t seen them in person, but he has visited rock paintings in Morocco, such as those in Oukaïmeden in Marrakech during his giant installations in the mountains, an experience he recalls as very enjoyable and highly inspiring for his work.

In hindsight, I connect with the philosophy of historical Romanticism and its awareness of the human sense of fragmentation, which led them in search of reconciliation of opposites, a yearning that became one of the pillars of André Breton’s Surrealism, with its tireless and profound exploration of the inner world. It was Carl Gustav Jung who ultimately resolved this conflict through the collective unconscious, connecting it with quantum physics. Therefore, I dare to draw a bridge between Mederic’s labyrinthine maps, which can be seen as a link to the collective unconscious through these totemic figures and African fables, all the way back to historical Romanticism, albeit with distinct steps and differences.

At Mederic’s request, I conclude this text with a quote from a great African writer, a defender of oral tradition known as the “sage of Africa,” Amadou Hampâté Bâ (1900-1991): “In Africa, when an old man dies, a library burns.”

Marga Perera, Ph.D. in Art History